Seeing Work Clearly

How understanding “normal work” can reveal risks, improve systems, and make the safer way the easier way

All of us try to find the most effective way to do our jobs, and we can expect the same of our staff and our organization’s leaders.

We do this because conditions, resources, and priorities are always shifting. For example, organizations (and the people in them) regularly navigate fluctuating costs, changes in weather conditions, staffing turnover, and changing schedules. Workers adapt and evolve the way they do their work in order to meet their goals, such as for safety or production, under the circumstances in which they are dealt.

Those adaptations are generally reasonable and are often essential, even if they don't match exactly the way a policy or procedure is written.

This concept is called “normal work” in contemporary safety science (Hollnagel et al., 2015). “Normal work” gives us a practical way to look at how work is actually done, so we can understand the adjustments and tradeoffs our staff and leaders make, and why those decisions often make sense.

In this post, we’ll apply this concept to outdoor and experiential education programs, and discuss how administrators who examine work from multiple perspectives can identify gaps and hidden risks, and make it easier for people to do their jobs well.

Varieties of Work

Steven Shorrock, an organizational psychologist and human factors expert from the aviation sector, describes a useful, four-part framework to understand work (Shorrock, 2016):

Work-as-imagined – How people think a job is done, based on their own understanding and mental picture of the work.

Work-as-prescribed – How the work is supposed to be done, according to written policies, procedures, and other official guidance.

Work-as-disclosed – How people say they do their work, which can be influenced by what people believe the listener wants to hear, or by what feels safe to share.

Work-as-done – How the work is actually carried out, with all the adjustments, compromises, and improvisations that make it possible under actual work conditions and circumstances.

Differences between these views are normal. They often reflect the reasonable adaptations people make so the work can succeed under the circumstances they face (Dekker, 2014). By examining work through all four lenses, we can better see where expectations match reality, where they drift apart, and where small adjustments could make the safer way also the easier way.

Mapping Normal Work

Once we know there are different ways of understanding and conceptualizing work, we can then make those differences visible.

Mapping work is one practical way to do this. This means literally writing out the various tasks that make up a work process, like the steps the program team takes to plan a program, or the process field staff follow to close a trip and de-issue gear.

As you sequence these tasks, make note of how the order of operations might differ; for example, details in the way staff describe their work might differ from the observations you make of them doing the work… which might also be different from the way these processes are outlined in the written policies and procedures.

Making these differences visible is important for risk management because it reveals where gaps, overlaps, redundancies, unnecessary complexity, and clutter exist.

In a recent program review I led, mapping a national program and looking for local program variabilities helped us realize that plans designed for multi-day backcountry expeditions were being applied to shorter, frontcountry community programs. The program planning process, as it was written and prescribed, was built for trips to remote areas, so it included steps like advanced wilderness medical training that made sense in the backcountry. However, these same steps were creating unnecessary burdens and delays in the urban programs where cost, time, and staffing resources were inherently different.

In another case, an organization’s child protection program sounded robust when it was described to me by various senior leaders, but mapping it on paper revealed that critical design and resourcing steps were skipped, which directly influenced the staff’s ability to follow their organization’s safeguarding policy.

Mapping also uncovers how barriers lead to workarounds.

And these workarounds eventually become normalized.

For example, I’ve seen local staff create their own medical screening process because the national system wasn’t built for the unique characteristics of their participant population. I have also seen teams stop doing pre-trip risk assessments altogether because they ran the same trip so often that the pre-trip paperwork felt futile.

In both cases, the workaround felt efficient and effective, and ultimately came to be accepted as “normal” by local staff. But, in both cases, these workarounds bypassed intended safeguards and allowed new risks to creep into the system unnoticed.

In short, mapping and articulating a more holistic understanding of work makes it possible to identify improvements that align with the realities of the people who actually do the work, rather than our assumptions about the context in which they do their work.

There are many ways to map work.

In my own consulting, I often use Hierarchical Task Analysis (HTA; Annett, 2003), a method I first learned in graduate school while studying systems-based risk assessment. Whether you use HTA or another approach, the goal is the same: to make the work visible in enough detail that you can have informed conversations about how it really happens, and what it would take to make it easier and safer to do.

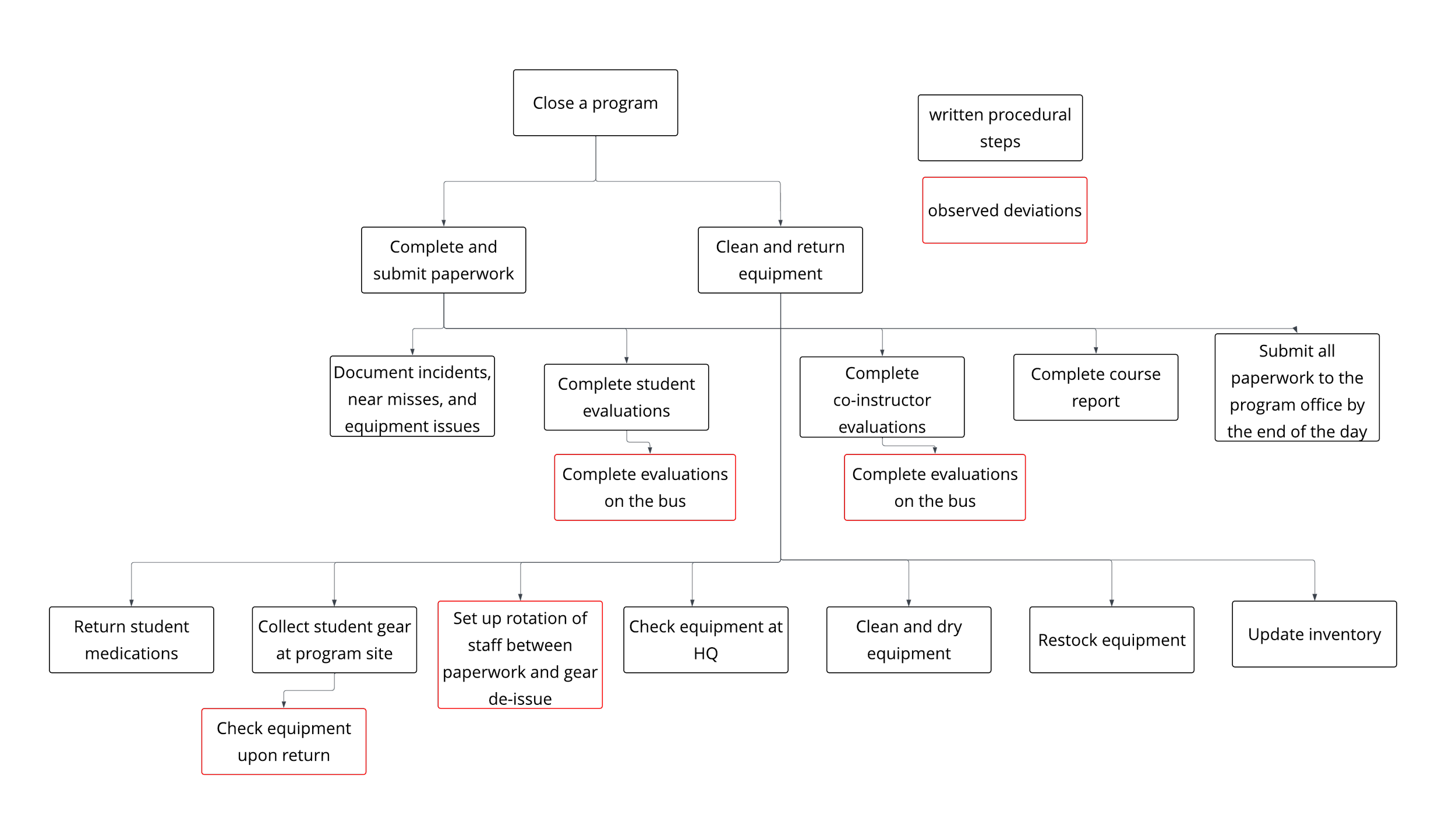

Example HTA showing the adaptations staff make to efficiently close a program.

Understanding all the various ways work is conceptualized and completed is not about pointing fingers and identifying errors.

Instead, it’s about understanding deviations and differences, and why those variations exist.

Once we train ourselves to recognize and understand these varieties of work, we are better at closing the gaps and creating better systems that meet the demands frontline workers face. By exploring these questions, you can start to identify which changes will make the process safer, simpler, and more effective. In some cases, the solution may be to update the procedure to reflect the way the work is actually done. In others, it might be to remove unnecessary steps, provide better resources, or improve certain safety controls at key points in the process.

Seeing work clearly is the foundation to meaningful and effective risk management.

Start by mapping one process in your program and compare how it’s written, how it’s described, and how it’s actually done, you might be surprised by what you learn.

References

Annett, J. (2003). Hierarchical task analysis. In E. Hollnagel (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive task design (pp. 17–35). CRC Press.

Dekker, S. (2014). The field guide to understanding ‘human error’ (3rd ed.). CRC Press.

Hollnagel, E., Wears, R. L., & Braithwaite, J. (2015). From Safety-I to Safety-II: A white paper. The Resilient Health Care Net. Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/signuptosafety/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2015/10/safety-1-safety-2-whte-papr.pdf

Shorrock, S. (2016, December 5). The varieties of human work. Humanistic Systems. https://humanisticsystems.com/2016/12/05/the-varieties-of-human-work/