One Way, Not The Way

How culture shapes the future of outdoor programming and experiential education

Young was plucked from an administrative job to help us find our bearings. It was a lateral move from one assistant role to another. But the jobs couldn't be any further apart.

It was the early days of our outdoor education program in Korea. The Korean government was building an international business district by dredging land from the ocean and putting a city on top of it. The city planners had approached several U.S. private schools, and the one I happened to work for as a seasonal field instructor was selected. Our job, as we understood it, was to bring outdoor ed from California to Korea. We didn’t know what outdoor ed could look like or mean in a Korean context. We didn’t even think to ask.

She had never been camping. My colleagues and I had never been to Asia. She translated Korea to us, from the trail signs and the maps to government rules and regulations. She did her best to explain and protect us against the unspoken rules and norms that were everywhere.

We translated outdoor ed to her. We explained what we were trying to achieve and why we thought the methods we employed were best. In turn, Young had to explain back to the government, the parents, and the locals what our thinking and intentions were.

By the time I left, nearly ten years later, Young and I joked that ‘we grew up together’ in those roles. No textbook, no training, no program back home could have taught us what we learned there.

Young, our original translator and cultural gatekeeper

That's where I began to truly understand that our approach to this work was one way, not the way.

We refined our approach over the years. We started teaching all instructors to read Korean. We hired more people with more Asian experience and knowledge. We went deeper each year in our instructor orientation to the country and culture. As interesting as it was, it always struck me that both Koreans and Westerners always commented that they learned more about their own culture rather than others’.

To develop a meaningful program in a cultural context different from our own, we had to cultivate empathy. Empathy across cultures is needed to better communicate and interact with each other. Cultural empathy is needed to understand the waters the other swims in. But to do that, you first have to understand your own.

This post offers a framework for that kind of learning. At its core, this post is about developing cultural empathy.

Cultural Risk

Culture is an indirect contributing factor to risk and safety. It helps explain the context in which decisions and actions happen, and why they make sense at the time.

That's what this series has sought to illustrate.

Cultural risk, then, is best understood as a systems phenomenon (Slay et al., 2025). It is in play much further upstream from individuals’ decisions and actions. It describes how social actors’ cultural perceptions shape their core beliefs and how these beliefs, in turn, interact with, and even conflict with, the design-logic of the system itself.

A cultural trait on its own is neither inherently good nor inherently bad. In fact, explanations about how culture impacts safety that only focus on people’s traits as a form of human error embody thinking that Harari calls culturalism (2015). Culturalism is similar to racism in that cognitive, physical, and perceptual limitations are suggested to be based on one’s culture (see Malcom Gladwell’s popular story about Korean Airlines for an example). Cultural risk is about understanding that the system itself is the unit of analysis, not individual perceptions and behavior.

When viewed in isolation, misalignments like a misinterpretation or a faux pas appear harmless at best and insulting at worst. When viewed as a whole, cultural risk helps explain how one group may perceive that a system negatively affects their overall safety and well-being, while another group may benefit from the full weight of security and safety intended by the system’s design.

Seeing cultural risk isn't just about reducing harm–although harm reduction is indeed a key goal. Each time our field makes strides in reducing harm, we make strides in becoming more meaningful and more relevant to our clients, participants, and to the communities in which we work.

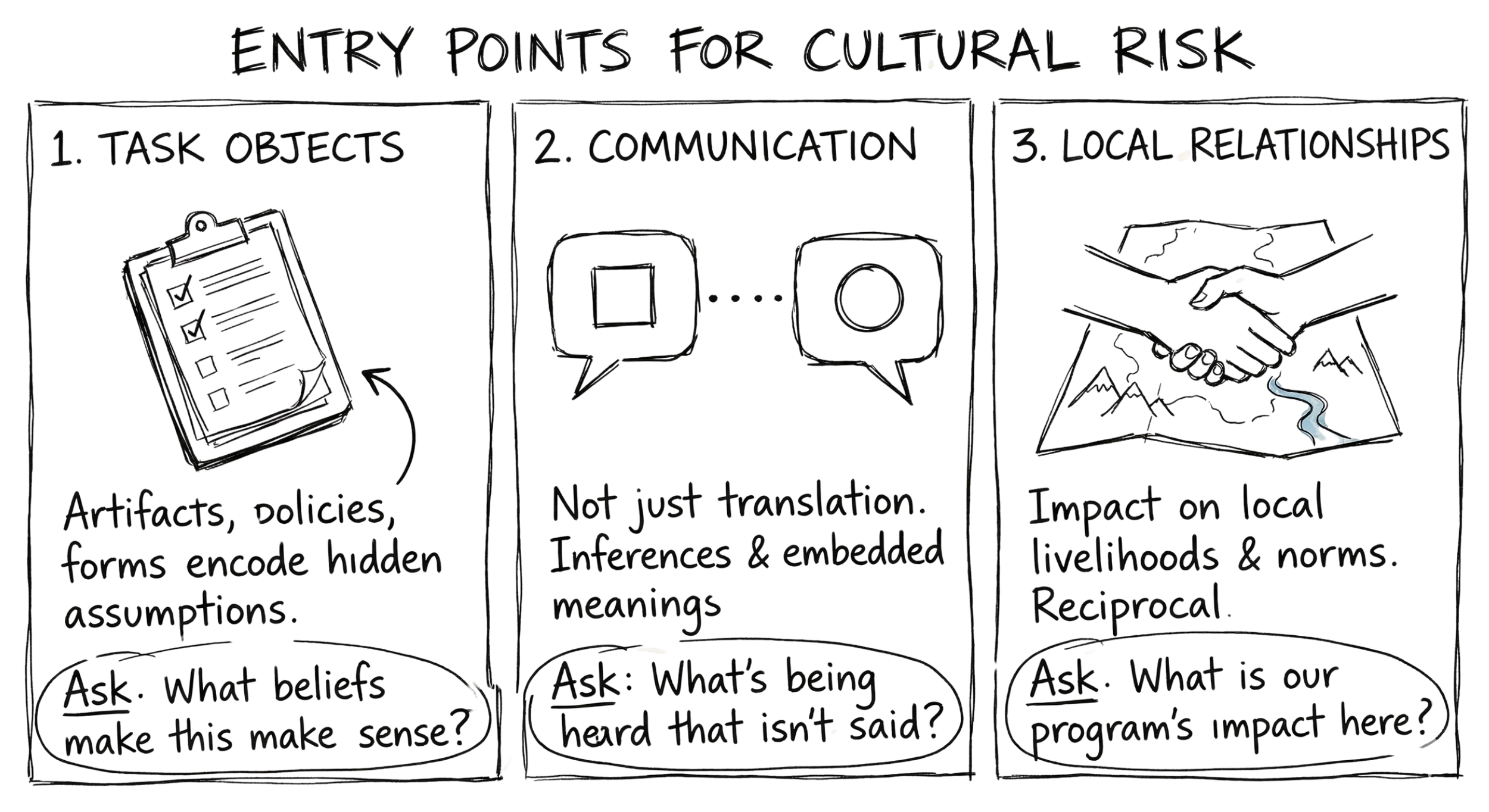

It’s hard for any practitioner to examine the behavior of an entire socio-technical system, and to contextualize its impact in their sphere of influence. In grad school, I found three places where cultural risk is introduced into a program’s system. These are the task objects, communications, and the relationships programs have with local people and the places they work.

These are the entry points, the places where you can start to see how culture shapes your program and its impact on others.

Task Objects

Task objects are the artifacts of everyday work: forms, policies, procedures, checklists, training curricula. They're not neutral. They encode the assumptions of whoever designed them, reflecting not just our intentions but our perspective on what problems need solving. When we standardize them as "best practices" and share them across the field, those assumptions spread. They persist year after year and program to program, without anyone questioning where they came from or whether they are adequately serving their intended purpose in a new context.

Ask: What would someone need to already believe for this policy or this document to make sense to them?

Communication

Cultural risk in communication isn't primarily about translation errors. It's about the assumptions embedded in the messages we send and the inferences made by those who receive them. Culture shapes not just how we communicate, but what our messages mean.

Ask: What's being heard that you're not saying?

Relationships with Local People and Places

Risk assessment typically considers the risks posed by local people and environments to our programs. It rarely considers what our programs pose to them. When programming is adverse to the livelihood, resources, or cultural norms of local people, relationships sour. Barriers are introduced to slow or complicate your work. Access may be denied, assistance may not be offered when needed, and local insights and knowledge may not be shared.

Recognizing the potential of our negative impact is part of the work.

Ask: What impact does your program have on the people and places where you operate?

Outdoor educators and risk managers are practical people. We want to know what to do. But in the case of culture, asking questions matters more than providing the answers.

Three ways cultural risk is introduced into the system

Transcending Paradigms

Seeing cultural risk isn't just about improving one program; it's about improving the collective understanding and practice of the field.

The more programs that regularly ask these questions and act on their findings, the more the mindset of the system expands.

Leverage points are places within a complex system where a small shift in one thing can produce big changes in everything else (Meadows, 1999). Changing the rules, the feedback loops, and the goals of the system are all meaningful leverage points, and continually refining these is a part of good risk management work. But the most impactful, and also the hardest one to access, is the one that underpins them all: the paradigm of the system itself.

Recognizing the mindset of an entire system offers potential for meaningful, paradigm-shifting solutions. If the cultural assumptions that constitute the design logic of the system are identified and aligned with the varied subjective, yet real, realities of the social actors involved, the system may actually have the power to transcend paradigms.

Recognizing that no paradigm is right is the first step. At the forefront of programming and safety should be the recognition that cultural perspectives are solutions, not barriers to managing risk. Programs should embody the local culture and environment as solutions to ‘good’ risk management, not hurdles.

Cultural risk isn't about seeing culture as a problem to manage. It's about seeing it as a resource.

Fifteen years in, I'm still learning to see.

References

Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The story of success. Hachette Uk.

Harari, Y. N. (2015). Sapiens: A brief history of humankind. Harper Collins.

Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage points: Places to intervene in a system. The Sustainability Institute, 1–19. http://drbalcom.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/35173014/Leverage_Points.pdf

Slay, S., Dallat, C., & Mitten, D. (2025). A cultural risk assessment of led outdoor activities. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership.