What I Learned About Experiential Education in a Korean Mountain Village

How culture shapes our blind spots

This story was originally published as a chapter in: Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging Field Guide: Stories of Lived Experiences (Association for Experiential Education, 2022). It has been adapted for this series.

"You're a neo-colonist with your experiential education ideas."

His words cut straight through me as I stared forward to the ground. Cho, my good friend who worked as our logistics manager, paused to recollect and continue the translation.

“You see, our current educational system came to us from Japan, by way of your American industrial revolution. If what you are describing is experiential education, it was here, on these farms and temples, and in these mountains long before you.”

I sat on his floor, cross-legged and knees aching. An uncomfortable silence divided the room.

The Gatekeeper

He met us at his door in Buddhist monk's robes, stepping past a stack of empty soju bottles he made no effort to hide. He was a small man, and when he spoke, he swore freely in what Cho later described as an "old-timey" way; he filled the room.

On his land, he grew gochu peppers and picked mushrooms. As a younger man, he nearly completed a PhD but decided the university hoops weren't worth the trouble.

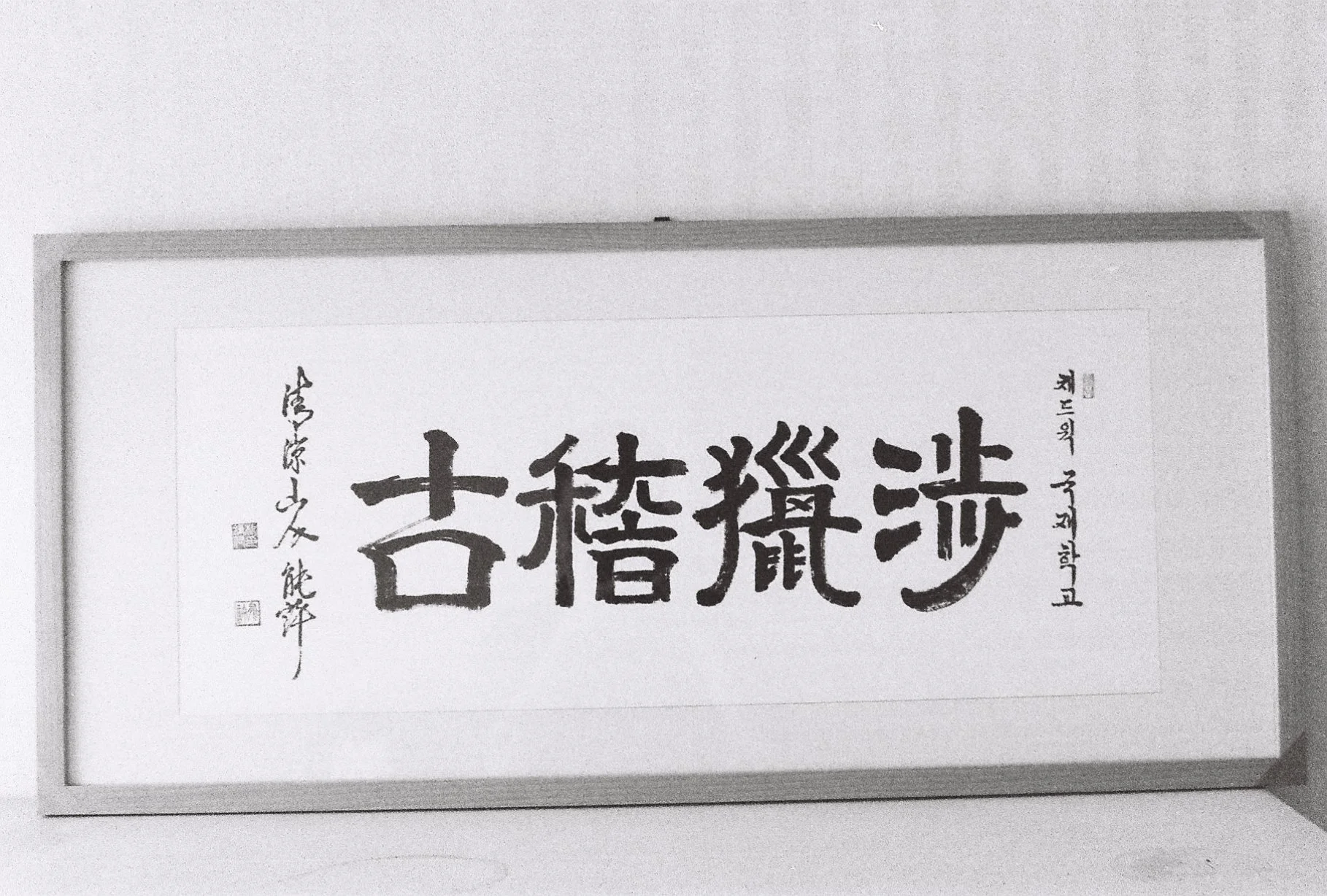

He called himself "Neung-ha," a pen name he signed to his artful and expressive calligraphy, which I still keep framed on my wall.

Neung-ha’s calligraphy, “At seventy, gazing at the sea,” reflects a view of learning grounded in lived experience, careful observation, and reflection over time rather than direct instruction or achievement. It still hangs on my wall.

As the town elder, Neung-ha held much respect within the small village of Wit-du-sil, a tiny mountain village of about 30 elderly farmers. During the Japanese occupation in the early 19th century, these mountains provided refuge for Korean partisans as they raided Japanese supply and transportation lines. Centuries earlier, kings and noblemen fled to these hills to rule in exile.

Today, the local villagers complain about the provincial park as a refuge for boars, who invade their lands and destroy their crops. A few villages further down the road, we met a woman who told us about the war between the north and the south, some 70 years ago. She remembers seeing American soldiers, but didn't realize there was a civil war in which the Americans backed the South until years after it was over.

In my history books growing up, the Korean War was sometimes referred to as "the forgotten war," if mentioned at all.

I had been on a years-long journey to find the perfect course area to support the program's curriculum—an area that could accommodate 6-8 independent student groups, with similar itineraries running simultaneously. The area we sought needed to have age- and skill-level-appropriate backpacking and paddling routes within scenic, ancient Korea.

This man, I knew, held the keys to these lands.

I was ready to engage him in every way possible to secure his support for our future courses here, including entertaining his life story, drinking and eating with him as friends, and discussing the merits of experiential education for the youth of Korea.

Going to School

I sat patiently and painstakingly listening as my knees ached and my back slouched. I stretched my legs out to give them a break as the message and its stinging intent passed around the room to my awaiting, English-only ears.

"Go on, tell him," I imagined him thinking.

"He says to sit up straight, and how dare you come into his room to slouch and stretch like a lazy miguk." Cho delivered his line flat and plainly.

I quickly recoiled and straightened up. I felt deep, shameful embarrassment over my offense.

"That is experiential education in Korea," he said. "You do. The teacher corrects. The student reflects.”

“What it means to be, to be yourself, and to be yourself in the presence of elders is different between the West and the East. By stretching out, you aim to comfort yourself. But to us, your stretching is loud, lazy, and selfish. I don't fault you for being or doing normal in your country, but you should show cognizance to what is 'normal,' here."

I sat tall but felt small. I became suddenly aware of my hands, my breathing, and the foreign weight of my own body in his space. My inner shame bore outward.

"The reflection is supposed to hurt," he said. "That's where the learning comes from."

"By coming here to claim you are 'bringing' experiential education to us, you are merely perpetuating the colonial tendencies and habits of mind our Japanese colonizers brought."

He stood up and picked an encyclopedia-sized book off his shelf. He studied it for a minute, found his page, then shoved it toward Cho. "Here," he said. "Take this home with you and study it. This article describes exactly that. You study it and translate it for him."

The book was a series of articles in Korean, Japanese, and Chinese compiled by a monk.

Some Time Later

I think about this day often.

What were we doing here? What purpose were we fulfilling by building a California version of outdoor education on the other side of the world? What assumptions was I bringing to this program that, if they were revealed to me, I would come to associate with deep shame and embarrassment (like getting comfy on this guy’s floor)?

I worked in South Korea for nearly ten years. What started as a curious adventure evolved into an eye-opening and life-shaping journey. Some lessons take years to sink in.

Neung-ha enthusiastically supported our program and was key to us keeping our access when the local government changed. After the first program there, the villagers confided how they felt joy at the sound of youth in the village after a nearly 30-year hiatus.

Our program leadership team, me, Cho, and JiHo.

References

Slay, S. (2022). Towards global inclusion and belonging. In R. Yerkes, D. Mitten, & K. Warren (Eds.), Diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging field guide: Stories of lived experiences. Association for Experiential Education.