Re-examining Mangatepopo

How culture shaped expectations, sensemaking, and decisions in a rapidly changing environment

The Mangatepopo Gorge tragedy is a landmark case in outdoor education. It is remembered, first and foremost, for the sheer scale of loss. Academically, it established that serious incidents in outdoor programs are better understood as systems phenomena rather than isolated errors (Salmon et al., 2010). That is why, when in graduate school, I chose this case to examine whether or not the cultural concepts I had been studying in safety science could be at play in safety incidents in our field (Slay et al., 2025).

What follows is not a rehashing of the accident investigation.

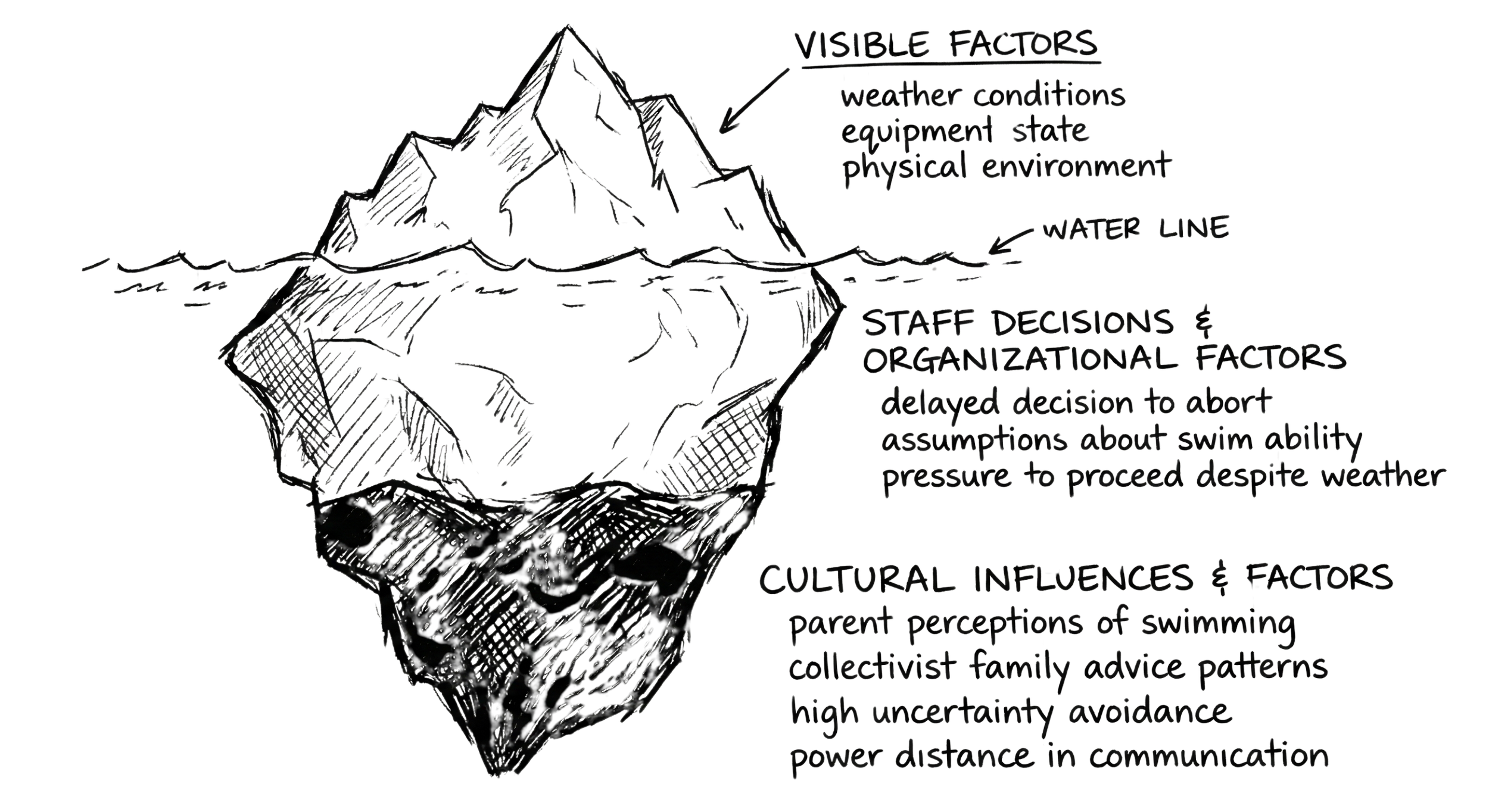

This post explores how cultural factors, often invisible and unexamined, can shape the decisions and actions that lead to catastrophic outcomes. The Mangatepopo is a story about how the systems we build, the assumptions we carry, and the cultures we operate within can either protect us or put us at risk.

The Incident

On April 15, 2008, a group of high school-aged students and their teacher entered Mangatepopo Gorge in Tongariro National Park, New Zealand, for a gorge walking activity run by a local outdoor program provider. What began as a routine adventure activity ended in tragedy when a flash flood swept through the gorge, claiming the lives of six students and their teacher.

The official investigation, led by Brookes et al. (2009), identified numerous contributory factors: inadequate swim assessments, incomplete parental consent, organizational pressure to proceed despite weather concerns, and staff experience levels that may not have been sufficient for the conditions. But beneath these findings lies a more complex story about how culture influenced each of these factors.

Understanding Incidents as Systems Phenomena

Before we dive into the cultural aspects, it is important to understand a foundational concept in contemporary safety science: systems thinking. Rasmussen (1997) argued that accidents do not happen because of single failures or bad actors. Instead, they emerge from the interactions of multiple factors across all levels of a system, from front-line staff to program management to organizational leadership and even government regulators.

Think of it like this: you can have the best instructor in the world, but if they are working within a system that prioritizes production over safety, provides inadequate training, uses flawed assessment tools, and faces pressure to push through adverse conditions, even that excellent instructor can find themselves making decisions that lead to tragedy. The problem is not the person; it is the context in which they are working. See my posts Systems Thinking Part 1 and Systems Thinking Part 2 for more.

This perspective is crucial because it shifts our focus from blaming individuals to understanding how the system creates the conditions for failure. And when we start looking at systems, we quickly realize that culture is embedded in every aspect of how these systems are designed and operated.

Swim Assessments and Cultural Assumptions About Water

Cultural risk emerges when the values, assumptions, and beliefs embedded in our programs do not align with those of the people participating in them. The Mangatepopo swim assessment provides a stark example.

Parents were asked whether their child was a 'confident swimmer,' without being told that potential swimming environments include moving water, deep pools, and cold temperatures. Their disclosures were neither tested nor confirmed by staff through an actual swim assessment. As a result, one participant's water-related fear went unacknowledged, and three non-swimmers were included in the group. Crucially, swimmers and non-swimmers were linked together as part of the fateful self-rescue plan.

Why would parents provide incomplete or inaccurate information? The answer lies partly in cultural factors that influence how different groups relate to water activities. Research (Irwin et al., 2011) indicates that individuals with limited access to aquatic facilities and swimming opportunities face higher drowning risks. In cultural groups where family advice is highly valued, this often results in children being discouraged from learning to swim and avoiding water activities altogether.

Collectivist and long-term cultural orientations, characterized by group harmony and the transmission of values across generations, can lead to strong family-based decision-making around activities like swimming. For example, these preferences may reduce the likelihood of learning to swim if parents oppose it. These cultural factors influence what information parents consider relevant when filling out pre-trip forms and whether their child will participate at all.

Uncertainty Avoidance and Rigid Adherence to Plans

Another aspect to consider in the Mangatepopo incident is uncertainty avoidance, the degree to which people prefer structure, rules, and predictability when dealing with uncertainty (see my post about uncertainty avoidance and situational awareness).

Cultures with high uncertainty avoidance, such as Greece, Japan, Mexico, and France, favor more rules and structure to minimize ambiguity. Inexperienced groups often share this trait, relying heavily on formal guidelines to manage risk (Aldjic & Farrell, 2022). While rules and procedures serve important purposes, strict adherence can hinder situational awareness and the ability to mentally reframe rapidly changing conditions. Leaders who follow rules too rigidly may find it difficult to adapt when circumstances change, potentially leading to delays in critical decision-making.

The investigation found that the program provider had a robust system of SOPs and training assessments for staff. That day, the group leader was highly enthusiastic about delivering the curriculum and was particularly focused on fostering group cooperation, as required by the unit standard. However, this dedication to the curriculum led to a delayed realization that weather and environmental conditions had changed, and the group's progress was slower than expected. In essence, the leader’s rigid focus on procedures and learning objectives may have hindered their recognition that the existing plans and SOP no longer suited the current circumstances.

Production Pressure and Organizational Priorities

Organizational culture was a major factor in the Mangatepopo incident. The investigation identified a pervasive 'rain or shine' culture in the program provider organization, and that it was fueled by financial and production pressures that pushed employees to accept bookings even when suitable staff were unavailable (see BLOG NAME for more about production pressure). Ultimately, these pressures and traits drove management to send the group into the gorge despite forecasts of heavy rain.

In national culture terms, Hofstede’s dimensions help us make sense of what might have been happening beneath the surface. Highly masculine cultures promote competition or target-focused behaviors, while short-term-oriented cultures prioritize immediate production gains over long-term safety interests. When both of these orientations interact, pressure to produce can become overbearing. It also happens that both of these orientations align with outdoor education's Western-rooted values, like pushing through limits for character development (see my post on Western Cultural Assumptions Embedded in Outdoor Education).

When an organization's culture prioritizes completing activities, meeting targets, and maintaining revenue over safety, those values cascade down through every level of the system. Staff feel pressure to proceed even when conditions are marginal. Concerns about weather or staff experience are weighed against the pressure to deliver the program as promised. And in that calculation, safety margins are diminished.

Power Distance and Speaking Up

Power distance, which is the extent to which people accept differences in status and authority, likely played a role in Mangatepopo. In high-power-distance cultures, challenging authority figures or disrupting the status quo is difficult. People are less likely to voice concerns, especially to those above them in the hierarchy (see my post about Speaking Up).

The Mangatepopo incident occurred within a context where established norms and leadership decisions can be difficult to challenge. For example, the organization was overconfident in its safety record, despite having a history of previous incidents in the gorge. High power distance reinforces 'the way we've always done things' and can limit an organization’s openness to learning from its past experiences.

This connects to the broader issue of safety voice, the willingness to speak up when something does not seem right. Safety voice is culturally informed. Cultural norms surrounding authority, hierarchy, and communication significantly influence whether individuals feel comfortable voicing concerns. Simply encouraging people to speak up is not enough if the cultural context makes that difficult or risky.

An iceberg model illustrating how visible conditions and decisions at Mangatepopo were shaped by less visible organizational and cultural influences.

Implications

The Mangatepopo tragedy is not a simple story of individual or even organizational, error. It highlights how cultural factors can impact safety at every part of a system. The swim assessments, consent procedures, decisions to go ahead despite weather warnings, and organizational pressure to run programs—all were influenced by cultural assumptions and values that were largely invisible to those involved.

What can we do with this information?

First, we need to recognize that our programs are not culturally neutral. The tools we use, the assumptions we make, and the values we prioritize reflect particular cultural paradigms. If we do not examine these, we risk creating mismatches between our programs and the people we serve.

Second, we need to build cultural competency into our risk management systems. This means more than just training staff to be culturally aware, though that is important. It means examining our forms, our procedures, our assessment tools, and our organizational cultures to identify where cultural assumptions might be creating risk.

Third, we need to create environments where safety voice can flourish across cultural contexts. This requires understanding how power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and other cultural dimensions affect communication. It means finding ways to hear concerns that may not be expressed in the ways we expect or are trained to recognize.

Most importantly, we need to recognize that safety is not just about managing equipment, environment, and people. It is about managing the interactions between these elements, and with attention to cultural context. And that requires a much deeper and more nuanced understanding of how culture shapes risk.

References

Aldjic, K., & Farrell, W. (2022). Work and Espoused National Cultural Values of Generation Z in Austria. European Journal of Management Issues, 30(2), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.15421/192210

Brookes, A., Smith, M., & Corkill, B. (2009). Report to the Secretary for Education on the safety of outdoor education programmes in New Zealand schools. Ministry of Education.

Irwin, C. C., Irwin, R. L., Martin, J., & Ross, D. (2011). Constraints impacting minority swimming participation. International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, 5(2), 127-145.

Rasmussen, J. (1997). Risk management in a dynamic society: A modelling problem. Safety Science, 27(2-3), 183-213.

Salmon, P. M., Williamson, A., Lenne, M., Mitsopoulos-Rubens, E., & Rudin-Brown, C. M. (2010). Systems-based accident analysis methods: A comparison of Accimap, HFACS, and STAMP. Safety Science, 48(10), 1298-1306.

Slay, S., Dallat, C., & Mitten, D. (2025). A cultural risk assessment of led outdoor activities. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership. https://doi.org/10.18666/JOREL-2025-12408