Struggle as Proof

How culture shapes common beliefs about challenge and outdoor education

It was a sandwich disaster.

In the first year of our outdoor education program in Korea, we set up an assembly line for about 80 fourteen-year-olds to pack their own lunches before heading out for the day’s activities. We laid out everything: bread, meat, cheese, lettuce, tomato, peanut butter, jelly, mustard, mayo….the whole works. It was the same, tried-and-true menu and sandwich factory from our sister school in California.

After a day of hiking, creek scrambling and nature walking, they all came back exhausted. In fact, they were too exhausted. The kids had completely bonked. At first, we just assumed it was a big day and we did a good job wearing them out. Then, an instructor noticed about 80 sandwiches in the trash with tiny, mouse-like bites.

How come nobody finished their lunch?!

Because they had put everything between their bread…peanut butter, lunch meat, mayo, jelly, lettuce, cheese, mustard….all the ‘fix-ins’ altogether. These kids weren’t sandwich artists. They grew up eating rice, kimchi, and kimbap, not sandwiches.

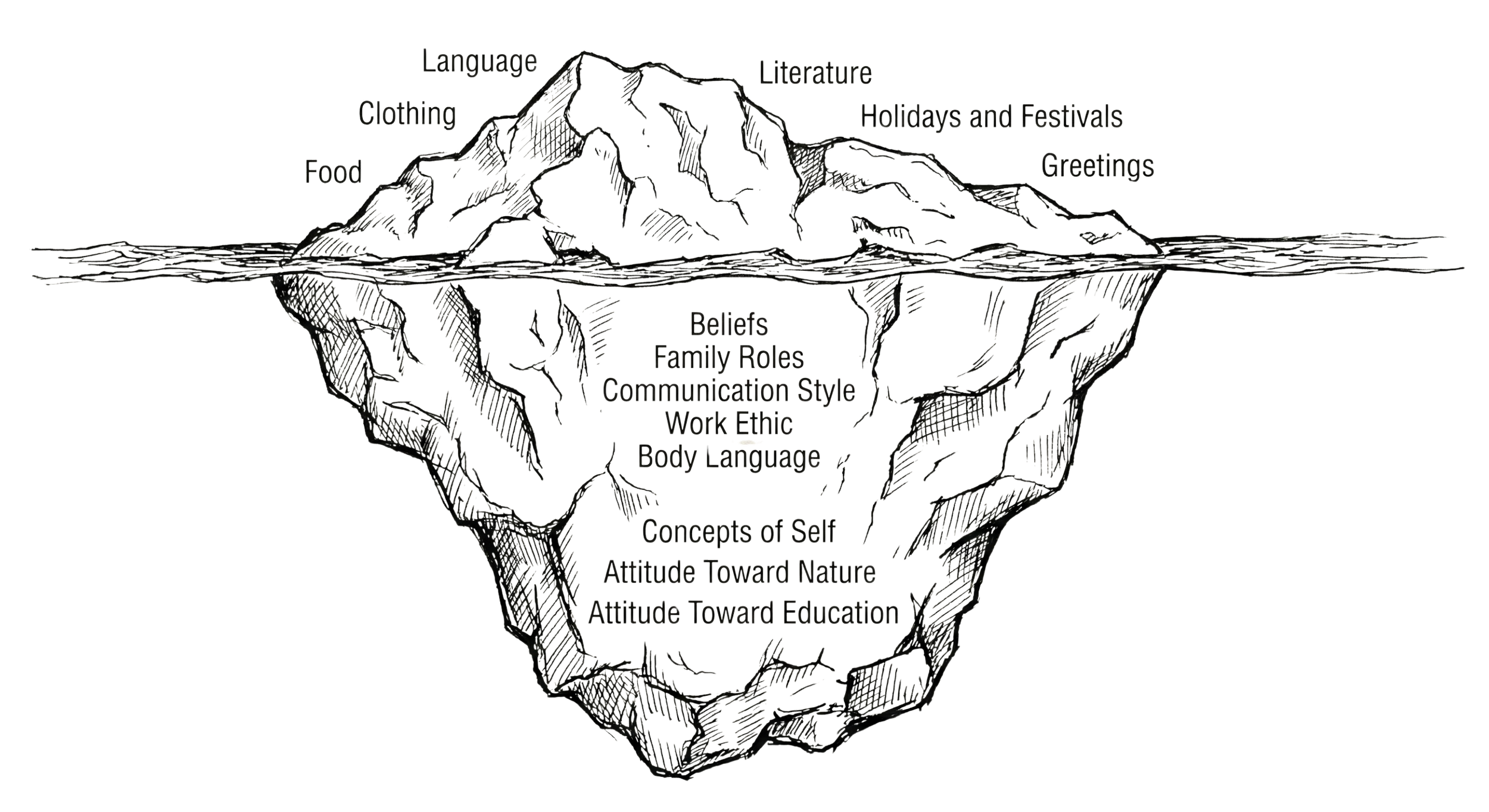

We fixed the lunch problem in time for the next year. But it pointed to something bigger. We were just at the tip of the iceberg that first year.

Outdoor education today rests on assumptions we rarely examine:

A relationship with nature as something to overcome and dominate.

A belief that adventure and challenge build identity and a strong sense of self.

A conviction that risk can be objectively managed.

These assumptions shape whose experience gets centered and whose gets ignored. This post and the next post in this series, called Through the Struggle, are about those three beliefs and how programs and participants benefit when those assumptions are questioned.

The cultural iceberg.

Nature as a Tool for Self-Improvement

In Western society (some would argue is now dominant, globally), nature is separate from daily life. It's a place you go to escape, rejuvenate, and to grow. We can look to the Return to Nature movement of the early 20th century, which positioned time outdoors as a cure for the ills of modern life and subsequently gave rise to organized youth programs like the Scouting Movement.

We design programs in the same vein, where nature is used to help discover your ‘true’ self, build character, and expand your comfort zone. These notions rely on a Eurocentric belief system about the human-nature relationship, in which nature is a classroom for self-realization (Becker et al., 2018; Warren et al., 2014).

The everyday language used by the uninitiated among us reveals this. We hear about “surviving the wilderness,” “hitting the water,” and “conquering the mountain,” all of which reflect the Western patriarchal tendency to dominate the natural world (Brookes, 2003; Mitten, 1985, 1994, 2017). Think: Go west, young man! and manifest destiny and all that…settling the frontier and taming nature and anything or anyone already there.

Nature as Relationship and Context

These are all symptoms of our ‘unhealthy attachment style with nature’ (Mitten et al., 2014). Instead of a reciprocal relationship, it’s one characterized by domination, insecurity, and instrumentality (use). In the Western world, nature is something we draw from, test against, and extract meaning from for our own benefit.

Indigenous, East Asian, and Buddhist traditions approach it differently. In those knowledge systems, people are a part of nature, not separate from it (Nisbett, 2004). Nature isn't a classroom for personal growth. It's the context in which you already exist. The moral task is alignment and harmony with nature, not conquest.

In Korea, we saw this contrast firsthand when we started working with Buddhist temples in the mountains. The monks could teach students about centuries of connection to those specific places. They knew the history, the spiritual significance, and the relationship their people had maintained with the land. We couldn't do that. We were still learning to read the trail signs and to pronounce the actual names of features and landmarks instead of making up our own, so we could safely lead groups. We were treading the waterline and learning the basics.

The dominant assumption baked into outdoor education today is that we take kids outside to build character through struggle with nature (Brookes, 2003; Brown & Beames, 2017; Mitten, 2017). That's a very Western reason for going into the mountains. It treats nature as a means to our own ends, as something that exists to serve our developmental goals.

These constructs and assumptions shape everything, from what we call adventure to how we frame challenge and define a successful program.

Developing the Self Through Challenge

Let’s talk about Western individualism. Actually, to stay with our relationship-with-nature theme, let’s call it rugged individualism.

‘Rugged individualism’ captures the way the Western self relates to the environment, challenge, and achievement. Because in the West, Westerners are the protagonists in their own movie plot (Nisbett, 2004).

A strong sense of self is distinct and consistent. Westerners typically like to stand out, and integrity literally means being the same person in every aspect and relationship of your life. Developing a sense of self means discovering what makes you, uniquely you, and it entails effort, personal action, and accomplishment. Growth happens when you push past previous perceived limits (Brookes, 2003; Hall, 1987; Mitten, 2017).

If achievement is the vehicle for self-discovery, then challenge is where change becomes visible. Perseverance and newfound competence are the measures of progress, and the outdoors and adventure are the perfect classrooms.

If participants are tired, frustrated, struggling, or otherwise stressed, there is visible evidence that something meaningful is happening. Development, then, hinges on whether the individual or the group acts, endures, and proves capability.

Implications in Korea

For years, we made students use shelters we knew were inadequate. We had imported mega-mid shelters from the US, but the poles we sourced locally weren’t the right fit (it’s a long story). The tarps sagged and collapsed. Bugs got in because there was no screen or floor. Students complained constantly.

Parents raised concerns, but we dismissed them. “They don’t get it,” we said. “They don’t understand what we’re trying to do. Discomfort and struggle build character and grit.” After all, we were the “experts” brought in from overseas to “bring outdoor ed to Korea (see my story post about Neung Ha).

At the time, our approach felt reasonable. The conditions were challenging, but the students just weren’t used to it yet. Students had to problem-solve and persevere, and they would eventually overcome it and bond over it. We’ve seen it before; it’s what we do in California.

Except we weren’t aware of our own assumptions. Rather than asking whether the mega-mid fiasco supported learning, we assumed our manufactured source of stress was dutifully serving as a vehicle for self-discovery and proof of individual and group development (read my post about common group development myths).

A Design Decision

Then one year, it clicked. Kids graduated, and they weren’t any better for having dealt with those droopy mids once a week every year. We gave in and replaced the mids with actual tents, fitted with the manufacturer’s poles, screens, a floor, and a rain fly.

The result? Social and eco anxiety dropped. Students slept better, and overall participation, engagement, and buy-in for the program improved. Students still faced challenges, but they were physically and mentally more equipped to navigate and learn from them, and the program was safer for it.

We mistook struggle for success.

Visible stress and anxiety were our signals that the program was working. Our expertise didn’t just shape our decisions; it shaped what we thought was worth questioning.

This way of approaching outdoor education felt natural because it was familiar. Familiar things rarely get questioned. At the time, we didn’t see our own beliefs and convictions as a set of assumptions; we saw them as the obvious way to design and lead programs.

The next post, Through the Struggle, explores what changes when those assumptions become visible, and what the outdoor education can gain in terms of safety and relevance.

References

Becker, P., Humberstone, B., Loynes, C., & Schirp, J. (2018). The changing world of outdoor learning in Europe. Routledge.

Brookes, A. (2003). A critique of neo-Hahnian outdoor education theory. Part one: Challenges to the concept of "character building". Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 3(1), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729670385200241

Brown, M., & Beames, S. (2017). Adventure education: Redux. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 17(4), 294–306. http://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2016.1246257

Hall, R. (1987). Linking resources, learning and experience in a multicultural world [Unpublished master's thesis]. Mankato State University, Minnesota.

Mitten, D. (1985). A philosophical basis for a women's outdoor adventure program. Journal of Experiential Education, 8(2), 20–24.

Mitten, D. (1994). Ethical considerations in adventure therapy. Women & Therapy, 15(3–4), 55–84.

Mitten, D. (2017). Connections, compassion, and co-healing: The ecology of relationship. In K. Malone, S. Truong, & T. Gray (Eds.), Reimagining sustainability in precarious times (pp. 173–186). Springer.

Mitten, D., D'Amore, C., & Ady, J. C. (2014). Human development and nature interaction. Working paper. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1059.9922

Nisbett, R. E. (2004). The geography of thought: How Asians and Westerners think differently... and why. Free Press.

Warren, K., Roberts, N. S., Breunig, M., & Alvarez, M. A. G. (2014). Social justice in outdoor experiential education: A new direction for change. Journal of Experiential Education, 37(1), 5–24.