Through the Struggle

How culture shapes our approach to trust and safety

In the previous post, Struggle as Proof, I described how, when I directed an outdoor education program in Korea, our program leadership and staff teams were influenced by a core system of intertwined beliefs:

Nature is a utility. In this case, for self-improvement.

Self-concept is encoded with individualism. Its development is best measured through achievement.

Challenge means struggle, which means pushing past one’s perceived limitations to reach the next level.

And, perhaps the biggest myth to take away from this post: As program designers and facilitators, it’s our job to create the conditions for challenge, and to push our students to overcome them (all struggle is good struggle, as long as no one gets physically hurt). In the end, they will become better people for it, having developed a stronger sense of self, the ability to work with others, and a connection to the natural world.

The Western cultural paradigm underpins those beliefs, and they influence the predominant approach to outdoor education. Those assumptions also lead to unnecessary and unhealthy stress for students.

These assumptions aren’t just a feature of my work at one international school. It informs the dominant approach to outdoor education and understanding of outdoor programs, globally.

Why These Assumptions Held

Let’s go back to why those assumptions persisted for so long, and why we were so slow to change course.

It took years to replace floorless, ill-fitting mega-mids with tents, despite consistent feedback from students and parents. We weren’t careless. We genuinely believed we were doing the best for students’ learning and development. After all, the shelters weren’t presenting safety-critical, life-or-death risks.

We held firm because our decisions were shaped by how we had been taught to assess and weigh risk. Industry peers and norms back home deemed a decision like this to be an acceptable trade-off. At the heart of the mids-versus-tents debate was the idea of beneficial risk. At the time, we believed the potential for learning and growth outweighed the downsides of discomfort, bugs, and anxiety. We could manage the physical safety risks, and we assumed that some level of discomfort was simply part of learning to sleep outside.

Our approach to programming and safety prioritized immediate, physical safety risks over students’ lived experiences. And in doing so, we overlooked that the two are inherently linked.

Expert Rationality and Objective Risk

Modern risk management is informed by a rational logic model that originates from ancient Greece (Nisbett, 2004; Zink and Leberman, 2001).

Translated to safety management, it means that rationality favors an objective assessment of safety. Decision, actions, and circumstances are either ‘safe’ or ‘not safe,’ and risks are either ‘preventable’ or ‘not preventable.’ Safety assessments, then, must rely on ‘expert' judgment, which is no doubt informed by the practitioner’s training and experience, and reinforced through peers and professional norms.

To be fair, this approach has advantages. It supports defensibility and accountability, but it also narrows our field of view. When risk is defined primarily through objective categories, perceptions and experiences that don’t fit neatly into those categories are easier to brush off. In this view, stress, anxiety, and diminished trust may be acknowledged, but they rarely register as risks in their own right. They’re too gray…too subjective and too contextual to sit squarely inside ‘safe vs. safe,’ ‘preventable vs. unavoidable,’ and ‘acceptable or unacceptable.’

This risk construct overlooks whether the activities and experiences are relevant to the program’s participants. Relevance shapes trust, and trust is the foundation of engagement and contribution.

The extent to which a participant’s experience is culturally relevant depends on how far they must bend their own relational orientation of self, others, and the environment to that of their program’s designers.

More practically, program designers should ask when and under what circumstances might we be asking participants to bend?

Participants cannot reliably contribute to the experience if they lack the requisite trust for their caregivers to provide the social, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual security they need to be seen and heard by their staff. Without trust, they cannot influence the staff’s engagement standards they need for their own success, and, consequently, their ability to take an active role in their own safety management is diminished.

Practically, the question for the field is this:

How can outdoor programs more effectively incorporate participants’ subjective experiences into programming and risk management?

Instead of asking participants for more, we should aim to enable more. We should aim to improve the context in which participants contribute their voices. We should strive for more awareness and conscious incorporation of multiple cultural perspectives in the design, planning, and facilitation of outdoor programs.

Subjective Experience and Risk

If risk management is informed by objectivism, what’s the alternative?

Subjectivism.

Subjectivism is rooted in Ancient China. Taoist thought, in particular, emphasizes relationships. If objectivism is about naming and classifying things (if not this, then that -logic), then subjectivism is about context and the relationships between things (Nisbett, 2004).

Relationships inform reason, logic, and truth, and serve to foster communal harmony within groups and society.

I’m not advocating that expert judgment disappears. Professionalism, industry norms, and staff experience are, indeed, the cornerstones. But ‘expert’ decision-making should be informed by people who are the experts in their own interpretations of their experiences.

From this perspective, anxiety, hesitation, silence, or withdrawal are not simply personal reactions suggesting the program hasn’t yet landed. They are signals about readiness, trust, and alignment between goals and expectations.

The contrast isn’t between expertise and relationships. It’s between narrow and expansive views of what counts as safety information. How a participant perceives their caregivers (staff), the program, and their experience is safety-critical information. When treated as such, expert judgement is more situationally aware.

This shift makes participants the drivers of their own safety and experience. To many, this is not a new aspiration; programs and practitioners have been working toward this shift for years (Yerkes et al., 2022). But perhaps by naming the shift and grounding it in its philosophical and cultural roots, we can accelerate and deepen both our understanding and our practice.

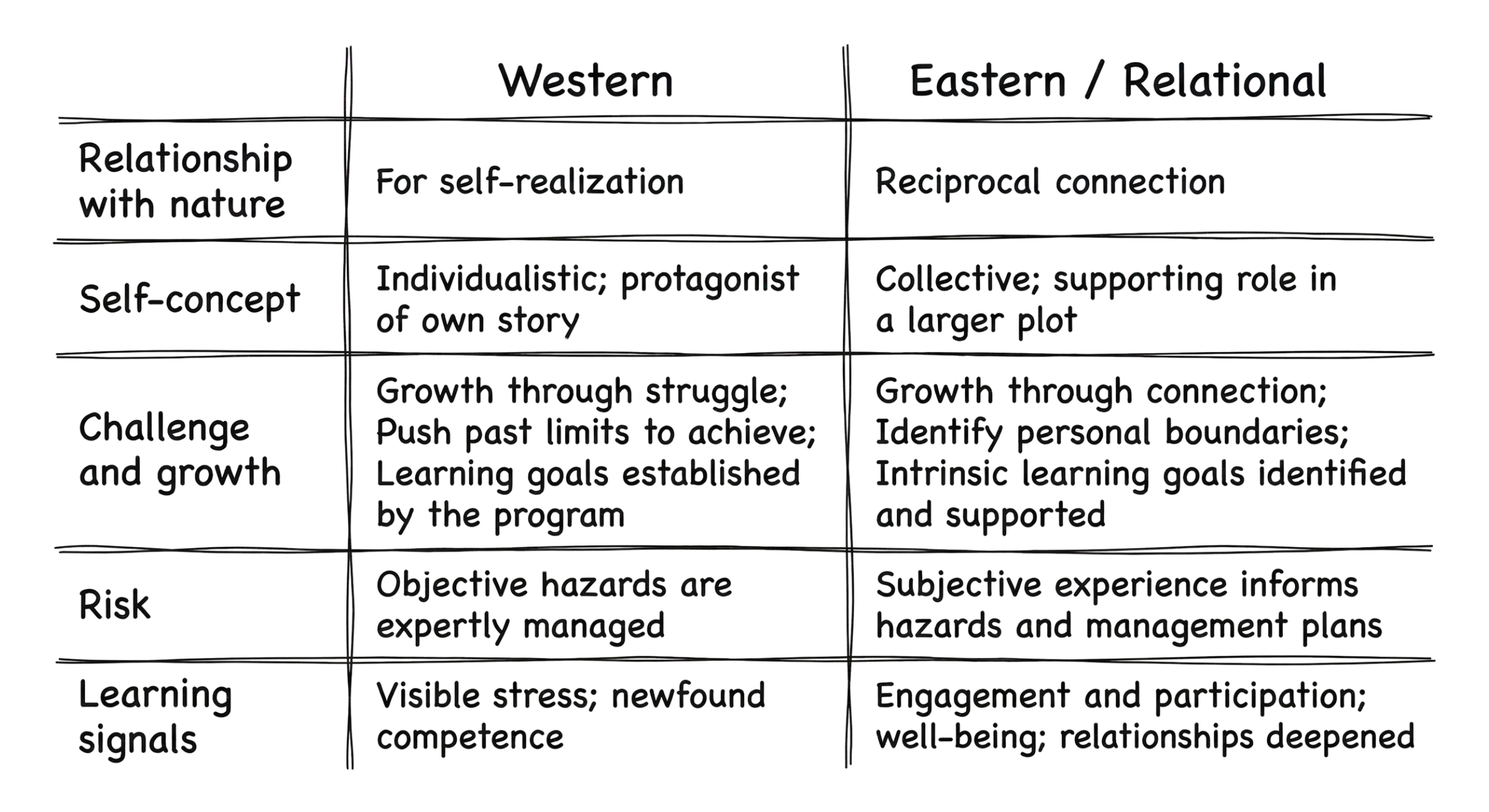

This table contrasts two cultural paradigms that shape how outdoor education understands nature, challenge, risk, and learning. The most effective programs integrate both, balancing individual growth with relationship, context, and care.

Expanding the Paradigm

Instead of programs being about developing selves through challenge, they become more about developing healthy relationships with the self and with others. Instead of using the natural world for self-discovery, programs become more about developing a healthy relationship with nature.

Challenge and Self-Concept

Adventure and challenge become ways for participants to identify, understand, and articulate their limits. Programming is not about pushing through one's limits but about identifying them. Only once boundaries are understood can they be expanded intentionally and safely, and in ways that align with both individual and group developmental goals shared by participants and program, alike.

This reframing also changes self-concept. Without awareness and reflection of one’s own sense of self and its roots, programs risk hegemony and exclusion. In other words, program designers should ask: whose sense of self is being developed, and whose is it modeled after?

By emphasizing relationships and personal boundaries, programs can expand the range of self-concepts they support. This creates space for both individual agency and relational forms of identity to coexist within the program’s goals. For example, in Confucianism, a person is understood differently depending on the relationship with others. One is not the same self with a parent or a teacher as they are with a peer, a sibling, or a subordinate. These different ‘selves’ are an important part of maintaining a harmonious society. While Confucianism is indeed old, these values and self-concept have bearing on East Asian life and identity today.

Nature

Turning to the environment, nature is no longer a utility for self-discovery. Instead, programs should aim to help participants foster a healthy relationship with the natural world.

Nature is not an instrument for development; it is a point of engagement.

The monks at the Buddhist temples knew the mountains in ways we never would. They knew the history, the names, the relationships their communities had maintained with that land for centuries. We were still learning to read the trail signs. We couldn't foster a sense of place with the students because we barely had one ourselves.

Thinking about culture isn't a question of what's missing. It's a question of what we have to gain.

I like to think about it in terms of health care. Eastern and Western medicines are starkly different: one is holistic and preventative, the other is reductionist and interventionist. We now understand that good health requires both. Outdoor programs are no different. They are more effective and safer when multiple cultural paradigms inform a holistic belief system that, in turn, shapes practice.

The sandwich problem was easy to fix. The assumptions underneath the iceberg took longer to see.

The outdoor programming community is small. Policies and plans get copied, staff rotate, and language gets repeated. “This is how we do it here” becomes “this is how it’s done.” The assumptions move with them, and they show up in gear lists, how we talk about challenge, and whose feedback we take seriously.

We couldn’t change our thinking because we couldn’t see the assumptions that informed it.

Now I see it everywhere.

References

Nisbett, R. E. (2004). The geography of thought: How Asians and Westerners think differently... and why. Free Press.

Yerkes, R., Mitten, D., & Warren, K. (Eds.). (2022). The diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging field guide: Stories of lived experience* [ISBN 978-0-9898710-2-0]. Association for Experiential Education.

Zink, R., & Leberman, S. (2001). Risking a debate: Redefining risk and risk management: A New Zealand case study. Journal of Experiential Education, 24(1), 50–57.